Everything and everyone adapts with age.

Even this oak found a way to surmount a host of obstacles,

not the least of which are the eroding cliff

it helps to shore up

and the hunk of rock that its root system worked around

for our photographing pleasure.

I have to learn to bite my tongue when someone suggests we

need to embrace our aging selves. This message can mean anything, of course,

from loving our wrinkles to merely accepting them. It can also mean stretching

them to oblivion a la Joan Rivers, whose embrace of aging was to eye it head on

and take heroic counter measures.

The version of the conversation that most rankles me has to

do with insisting that we like how we look as we get older.

We change but our aesthetics don't. I prefer the picture of the Rae of 1977 to

the picture of Rae in 2014. Sometimes I see a current photograph of myself I find

acceptable. It has a lot more to do with lighting than with me, though. And

when it comes to naked sex, who doesn't love candlelight?

Aging is hard. We’re not expecting it. We

don’t understand what’s happening when it starts to make itself known. And most of our

loved ones who are aging do so in quiet dignity for lots of reasons. Thus, we are not privy to vital wisdom that might inform this last leg of

our journey.

And it is the last leg, long and fit and handsome as it might

be in this moment, it is a leg that is going to give out — most likely little

by little.

This week I reviewed Boston surgeon Atul Gawande’s must-have

new book, “Being Mortal.” He lays out the aging process and what he says are

the inevitable infirmities to come. Part of his message is that it’s best to be

informed and prepared. But it’s also best to work toward living the fullest

life you can up until the last breath. He says it’s not the good death we’re

after here but the good life.

So what does my good life look like? It looks like a lot of

time spent staying active, fit, well nourished and engaged. As I lose muscle,

which has already happened and will just continue to happen, I do what I can to

counter that inevitability. I am 66 and can still jog. I don’t say that with

pride but with a certain trepidation. Every run ends with a thank you prayer to

the universe and to my body. I don’t want to take anything for granted. I don’t

want to feel smug about what is merely a gift. I don’t want to forget my

underlying vulnerability and make a misstep that will set me back weeks, months

or more.

How are Gawande and facelifts related? Because anyone who

has a facelift has gone through a process of evaluation and reckoning. That

person is looking at aging and saying: I am looking old and I’m going to do

what I can to look the way I want to look in my oldness. That person pulls off

the bandages and says: Call me empowered. I am doing it my way.

Joan Rivers was uncompromising in her push to live the good

life. I saw her speak at Barnes & Noble two years ago and they practically

had to drag her off the stage, she was having so much fun entertaining us with

her stories.

"My makeup team is nominated

for 'Best Special Effects'."

Rivers persisted according to her own code of conduct. Right

up until her last breath. It wasn’t easy, as anyone who’s read about her or

who’s seen the recent documentary “Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work” knows. But she

did what Gawande might have liked — she figured out how to do what made her

happy in an aging body and she did it.

The Golden Rule, as some of us know, is flawed. It’s

narcissistic. It’s not “Treat others as you wish to be treated.” It is: “Treat others as they would like to be treated.”

Finally, when someone tells me to embrace my aging body, I

need to stop and take a breath. What about what she’s saying am I’m not

hearing?

Questions:

- Do we need to like our looks to be holistically happy?

- If we accept aging, will we then like our appearance?

- Is attitude subject to the same timeline as aging? Perhaps

I, too, will someday like what’s before me in the mirror?

- Is it fair to ask an old person or a fat person to celebrate

their body? In other words, how independent are we from the social norms that

shape us? And isn’t my aesthetic, formed long ago, still valid even if I no

longer reflect my own aesthetic?

I’d love this conversation to keep going. Please respond if

you’re interested.

Below is my review of "Being Mortal" by Atul Gawande:

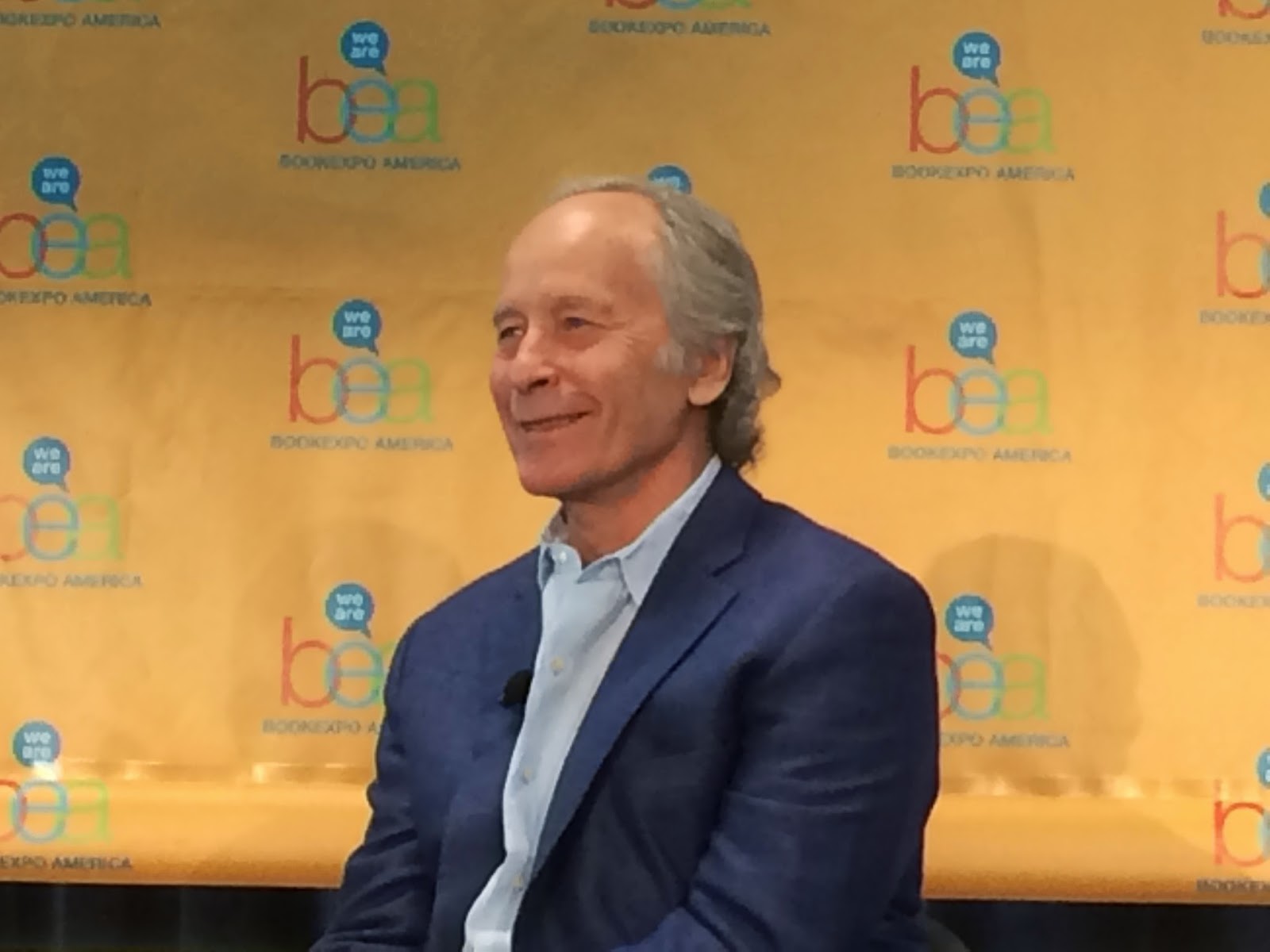

Atul Gawande: "Our reverence for independence

takes no account of the reality of what happens in life."

'Live for now'

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End

By Atul Gawande. Metropolitan Books, New York,

2014. 282 pages. $26.

Society is slow to change. We’ve learned how to

treat diseases and conditions that, in the past, killed us well before our hair

turned gray. But now that we know what to do, we don’t know when to stop doing

it. Medical solutions are not always the best solutions. And yet “fix it”

remains the mantra even when fixing it threatens great risk to quality of life.

Boston surgeon Atul Gawande’s new and important

book, “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End,” talks about the

monumental change our society is undergoing with regard to how we care for the

terminally ill, the aging and the infirm. He cites studies that highlight

assisted living and hospice models that focus on “a good life to the end.” These

models cost less, and they yield greater quality and length of life. Yet there

has been no national call to action. As Gawande shows, there are alternatives

to the traditional nursing home or ICU death that work and work well.

One hopes, when contemplating this must-read book,

that “Being Mortal” will spark a vigorous national discussion and produce immediate

imperatives. Gawande’s earlier book, “Checklist Manifesto,” about how to

curtail hospital practices that lead to infections, among other things, was such

a call to action.

"The story of aging is the story of our parts."

— Atul Gawande

Gawande’s parents, who immigrated to Athens, Ohio,

from India, were also doctors. Yet all three of them were at a loss when

confronted with his father’s end-of-life issues. In “Being Mortal,” Gawande

introduces us to people who were in their declining years or who were suffering

terminal diseases. He shows us how they made medical decisions, and when and

how they transitioned from seeking a medical solution to finding value in their

last days and weeks. While all the people he follows in this book are

affecting, none is more so than his father, who discovers he has a large tumor

growing in his cervical spine. Options are limited and some options had the

potential to severely restrict his father’s independence with consequences like

paralysis. How far are you willing to go just to be alive?

Modern medicine has the potential to bring with it

“new forms of physical torture,” writes Gawande. Anyone with a dying loved one

who winds up on life support in ICU understands. There are no last words in the

modern deathbed scenario, just a shutting down of machinery. Through hard

questions and with the help of trained professionals like hospice workers, it’s

possible to consider other options.

Gawande lays out the problems and the options. In

1945 most deaths occurred at home. In the 1980s, only 17 percent of deaths

occurred at home, and those were most likely due to the fact that they were

sudden, like heart attacks or injuries. On the plus side, in 2010, about 45

percent of deaths occurred with some kind of hospice care. But half of Americans

are likely to spend one or more of their last years in a nursing home and this

option is usually devastating.

“The waning days are given over to treatments that

addle our brains and sap our bodies for a sliver’s chance of benefit. They are

spent in institutions — nursing homes and intensive care units — where

regimented anonymous routines cut us off from all the things that matter to us

in life,” writes Gawande. “We have allowed our fates to be controlled by the

imperatives of medicine.”

We revere independence, regardless of our medical

condition. What happens when it can’t be sustained, asks Gawande? And yet, “serious

illness or infirmity will strike. It is as inevitable as sunset.”

Gawande touches on one problem I see all too

often. “We feel as if we somehow have something to apologize for” when the body

starts to fail. Gawande briefly describes aging. Since no one likes to talk

about these things, he does us a service explaining what’s happening to us and

our loved ones. Some processes can be slowed with diet and physical activity, but

they can’t be stopped. Things shrink, harden, leach, calcify and shut down. Aging

most likely follows the classic “wear-and-tear” model more than genetic

predetermination theories.

"The mantra was: live for now."

Our priorities are terribly askew. There aren’t

even enough geriatric doctors to replace the ones who will retire and yet our

elderly population grows and persists. In 30 years there will be as many people

under 5 as over 80. Right now there are as many 50 year olds as 5 year olds.

In many ways, geriatrician Juergen Bludau

encapsulates the main message of this book: The job of any doctor is to support

quality of life — freedom from the ravages of disease as much as possible and

retention of enough function for active engagement in the world.

This is precisely the mission of geriatric and

hospice care.

Much of the value of its book is in its very existence.

It gives us a place from which to continue the discussion. Also valuable are

the many anecdotes Gawande gives us — stories of people who are making a

difference, either by their own examples or in their groundbreaking

entrepreneurial efforts.

Among these is Keren Brown Wilson, who started the

first assisted living home in Oregon in 1980s. It caught on like wild fire, of

course. And there’s Bill Thomas at the

Chase Memorial Nursing Home in New Berlin, NY.

After wrangling with a lot of red tape, he brought birds, dogs, cats and a

garden into the daily lives of the people in this nursing home. Harvard-trained

and a “serial entrepreneur,” he “put some life” in the nursing home and people

who hadn’t spoken started speaking, while others started walking. “The lights turned

back on in people’s lives,” writes Gawande. It was like “shock therapy” for everyone involved. The

number of prescriptions dropped by half and deaths dropped by 15 percent. “The

most important finding was that it is possible to provide [people] with reasons

to live.”

"We're caught in a transitional phase."

In the United States, 25 percent of all Medicare

spending goes to the 5 percent of patients in the final year of their life and

most of that money goes for care in the last couple of months. Whereas the

hospice mission conveys a different message: Live for now, not what may be

possible with more risky surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation.

Decision-making is very difficult, with 63 percent

of doctors overestimating their patients’ survival time on average 530 percent of

the time. And forty percent of MDs admit to offering treatments they know are

unlikely to work.

“Those who saw a palliative care specialist

stopped chemotherapy sooner, entered hospice far earlier, experienced less

suffering at the end of their lives— and they lived 25 percent longer.” It’s

Zen, says Gawande. “You live longer only when you stop trying to live longer.”